“The thread”

How to join statements and sentences and to make transitions

A good English text has a very clear structure

Introduction

One of the main characteristics of a good text in English is that it has a clear line of thought and that as readers we always know where we are in the story the text is telling, and what the text wants to communicate. In some languages, we call this “the thread”.

This text explains techniques to establish a so-called “thread” throughout a text with a focus on paragraph structure. A paragraph is a series of sentences that are organised and related to a single topic. The text will do so by discussing three principles of text organisation: paragraph structure, theme-rheme structure and cohesion/coherence. These principles are basic, overlapping features of well-structured expository texts and they should be seen as complementary and not as mutually exclusive features.

A good paragraph structure helps readers follow your points

Paragraph structure

Careful structuring of paragraphs is important because it helps readers follow your points. A text paragraph has three parts: a topic sentence ,which is usually found at the beginning of the paragraph; the body of the paragraph, which consists of supporting sentences that provide details to support the topic; and the last sentence in the paragraph, which is the concluding sentence that summarises the paragraph.

The first sentence in a paragraph is a topic sentence with a controlling idea

The topic sentence pinpoints the focus of your paragraph

The topic sentence sets expectations; and to determine what the topic sentence should be, you may want to think about the information you wish to communicate, the points you want to focus on, and the issues or arguments you want your readers to accept or understand. The answers to these questions will likely hold the key to the topic sentence. Writing up a series of topic sentences for the Introduction and the Discussion may also be a way of helping you organise your thoughts when you a writing a scientific paper.

A topic sentence limits the topic

A topic sentence states the topic and the most general idea of the paragraph, i.e. it both mentions and limits the topic. An example of a topic sentence that is sufficiently broad while at the same time adequately limited could be: Cancer (topic) is the second leading cause of death in Denmark (controlling idea). Reading this sentence in the beginning of a paragraph, the reader knows that this paragraph will be about cancer mortality in Denmark. Another topic sentence could be Our study has several important strengths; a topic sentence that tells the readers that now you will discuss the various strengths of your paper.

New points or perspectives require new paragraphs

The body of the paragraph consists of supporting sentences

Supporting sentences

The body of the paragraph consists of supporting sentences, i.e. sentences that explain, prove or develop the topic sentence by giving more information about it. There are several ways in which supporting sentences may develop your topic through an ordered progression of ideas. Adequate paragraph development through the use of supporting sentences may consist of the use of examples and illustrations, citing of data, comparison and contrast, evaluation of causes and reasons, analysis of the topic raised, or a simple process paragraph involving a straightforward, chronological step-by-step description.

Supporting sentences develop the topic

Supporting sentences may be coordinated or subordinated sentences or separate main sentences; i.e. whatever best suits the expository purpose and the writer’s aim. The important thing is that they all relate to the issue raised in the paragraph’s first sentence, the topic sentence. Examples of simple main sentences supporting the topic sentence mentioned above could be the following: Lung cancer is responsible for the largest number of cancer deaths. Breast cancer is the most common form of cancer among women, and prostate cancer has become the most common cancer among men. Evidently, to establish a flow in a paragraph, these sentences need to be connected; how to do that will be discussed below under the heading Cohesion and coherence. For now, the important thing to note is that every supporting sentence must relate to the topic and the controlling idea. presented in the first sentence in the paragraph.

Paragraphs are often one-third to two-thirds of a double-spaced page

The supporting sentences constitute the body of the paragraph, and paragraphs may obviously be of varying length depending on the extent to which the topic is developed. Paragraphs are usually between one-third and two-thirds of a double-spaced page. If they become too long, they tend to be difficult to read, and they should be broken up into smaller parts with logical shifts. from one to the next paragraph. Short paragraphs of three to four sentences should be avoided. So, if you have many short paragraphs, try to combine them if they address the same topic or try to develop them further.

End the paragraph with a concluding sentence

Concluding sentence

The last sentence in a paragraph should be a concluding sentence. It should take the form of a main sentence that signals the end of the paragraph by summarizing the main points or repeating the topic sentence; for example: Thus, mortality rates shown that cancer is the second leading cause of death in Denmark.

The text flows from known to new infor-mation

Theme and rheme

Theme = topic Rheme = controlling idea

Most sentences – in English like in other languages – have two parts: a theme (topic) and a rheme (comment). Referring to the presentation above, we may say that the topic sentence signals the main theme and the main rheme of a paragraph. In the sentence Cancer is the second leading cause of death in Denmark, the topic is the theme (cancer) and the controlling idea is the rheme (is the second leading cause of death in Denmark).

Theme is what we talk about; rheme what is being said about the theme

The theme is what the text talks about, which will often be the subject phrase of the sentence; the rheme is what the text says about the theme, and it is often ifound in the verb phrase. In English expository writing, which aims to explain or describe a situation, the theme is usually the point of departure of a clause; its position is usually the initial position in a sentences. The rheme is where the presentation moves after the point of departure; its position is that following the initial positon, or at the end of the sentence.

Colour the themes

In the drafting stage, you may find that the flow of your text stands out more clearly if you use colour or bold to identify the themes. Let us look at a sample sentence (an Introduction) where the themes are in bold:

Cancer is the leading cause of death, and the risk of getting cancer before the age of 75 reaches 30% for men and 26% for women in the Nordic countries (ref). Lung cancer has a particularly high incidence, and mortality from this disease is largely determined by its stage at diagnosis: differences in survival between stage 1-2 and stage 3-4 cancers thus reach 50 percentage points (ref). Danish citizens are generally diagnosed with cancer at later, more advanced stages than other Europeans and therefore have inferior cancer survival rates. For lung cancer, for example, the Danish relative 1-year survival rate was 34.9 compared with 43.6 in Sweden in 2005-2007.

Plan the flow of themes

To clarify the flow of information, i.e. the thematic structure, you may find it a good idea to first draw up a plan showing the flow of themes and to use colour or bold o identify the themes and the rhemes. You may do so by simply writing a number of one-liners where the theme is fronted. For the above text, these one-lines could be as shown in the table below. Note that sometimes one theme has two rhemes; e.g. the theme Danish citizens has two rhemes: 1) diagnosed with cancer at later, more advanced stages and 2) have inferior cancer survival rates. Note also that at this planning-your-text level, the rheme should be boiled down as much as possible, i.e. there is no need for the sentence to be complete and grammatically perfect.

| Theme | Rheme |

|---|---|

| Cancer | is leading cause of death |

| Risk of cancer before age 75 | is 30% for men and 26% for women in the Nordic countries |

| Lung cancer | has a particularly high mortality |

| Lung cancer mortality |

is determined by stage at diagnosis and survival differences reach 50 percentage points |

| Danish citizens |

are diagnosed with cancer at later, more advanced stages have inferior cancer survival rates |

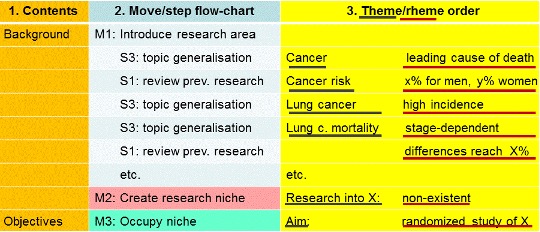

Once the one-liners have been made, you may later reorder them to make sure that the thematic progression is as you want it to be, and you may decide on how the sentences should linked – either coordinated or subordinated. You may also find it useful to integrate the theme-rheme table into a larger table showing how the themes are organised in moves and steps and aligned with the research-specific guidelines. In the figure opposite, the first column shows which elements must go into the Introduction subgenre of a paper reported according to the Consort checklist. The second column shows the moves (M1-M3) and the steps in M1 (S1-3); the third shows the theme (black underlining) and the rhemes (red underlining).

Three kinds of thematic progression

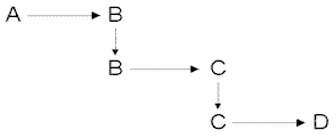

In progression with linear theme, a theme repeats or transforms the rheme of the preceding sentence

Linear progression

In thematic progression with a linear theme, a theme repeats or transforms the rheme of the preceding sentence. We may illustrate this as shown in the figure.

This kind of thematic progression is often found in Introduction and Discussion sections. In the Introduction above, we have a linear thematic structure. Let us consider another, simpler example:

Extremely premature childbirth has a well-known adverse long-term impact in the form of immaturity and proximal complications that may give rise to cognitive, educational and behavioral problems at school age. Adverse outcome assessment is essential to trace family factors that may help improve treatment and guide intervention efforts. The family impact of extremely premature childbirth has attracted much interest in recent years.

In this example, the rheme of the first sentence (adverse long-term impact) is thematised (adverse outcome assessment) in the second sentence; and the rheme of the second sentence (family factors) is thematised in the third sentence (family impact). In this way the theme gradually develops.

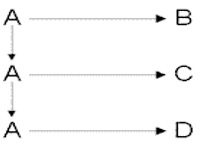

In progression with constant theme, the same theme is repeated at the beginning of each sentence

Progression with constant theme

In progression with constant theme, the same theme is repeated or slightly rephrased at the beginning of each sentence. We may illustrate this as shown in the figure.

This kind of thematic progression is often seen in Materials and Methods sections. Let us consider an example:

Selected characteristics of children, listed according to history of myocardial infarction in their parents are shown in Table 1. Children whose fathers reported a myocardial infarction were most likely to be white, to smoke cigarettes, to be older, and to be obese, than were children whose fathers did not report a myocardial infarction. In contrast, although children whose mothers reported a myocardial infarction tended to be older, no statistically significant differences relating to the disease was observed.

In this example, the theme of the first sentence (Selected characteristics of …) is thematised in the first sentence stating the general results. In the second sentence, the theme is one subgroup (children whose fathers…); in the third sentence, the theme is another subgroup (children whose mothers). With this structure, the thematic focus is maintained.

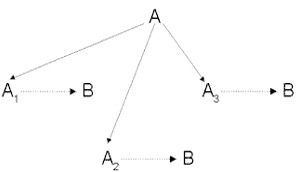

In progression with a derived theme, subsequent themes are derived from a superordinate theme at the beginning of a paragraph

Progression with derived theme.

In progression with a derived theme, subsequent themes are derived from a superordinate theme at the beginning of a paragraph. We may illustrate this as shown in the figure opposite.

An example: Several features of the outbreak (A) are of importance: First, after four years there is no evidence that the outbreak (A1) is waning. Secondly, the age distribution of cases (A2) is unusual by comparison with recent national data. Thirdly, throat swabbing (A3) revealed a very low carriage rate of B:15 meningoccoci in symptomless contacts

In this example, the superordinate theme (A) is several features in the first sentence, from which three subordinate themes are derived: A1: the outbreak; A2: the age distribution of cases; and A3: throat swapping, each of which has separate rhemes (red text).

You may read more about theme/rheme structures in particular text types here.

Writers must be explicit in making their texts coherent

Cohesion and coherence

Coherence is a product of many different factors that combine to make every paragraph, every sentence and every phrase contribute to the meaning of the whole piece. Coherence in writing is much more difficult to sustain than coherent speech because writers have no nonverbal clues to let them know if their message is clear or not. Therefore, in written texts, we must make patterns of coherence more explicit than in verbal texts, and we must carefully plan the text.

Cohesion is the linking of sentences through the use of linguistic elements

Most basic guidelines for building a good text with a clear line of thought recommend that you use both cohesion and coherence. Cohesion and coherence are two sides of the same coin. A text is cohesive if its elements are linked together; and it is coherent if it makes sense. Cohesion, in other words, consists of linguistic elements (within the text) binding sentences together (e.g. and, therefore, etc.). Coherence is the text’s relationship to the social and cultural context of its occurrence; we may say that coherence is logical links at the ‘idea’ level. When we combine the two, we get texture or what was described as the “thread” in the beginning of this text.

Link everything

Basic guideline for creating texture

Put very simply, textual cohesion and coherence – or texture – is obtained by linking all parts of the text, i.e. by linking each sentence to the previous sentence, linking each paragraph to the previous paragraph, linking each section to the previous section and linking the end to the beginning.

Pronouns, repetition of words connecting words

Linking techniques

Whether you want to link clauses, sentences, paragraphs, sections or the beginning of the paper to the end, you can use three basic linking techniques 1) pronouns (called grammatical cohesion); 2) repetition of key words (called lexical cohesion); and 3) connecting words (called lexico-grammatical cohesion).

Pronouns smooth sentences and help keep focus

Pronouns

Pronouns (it, they, this, that, these, those and which) add coherence to a paragraph in two basic ways. Firstly, they smooth the flow of the sentences by eliminating awkward repetition of nouns, and they help to knit a paragraph together by referring to nouns in previous or subsequent sentences or sentence parts. It is important, however, only to use pronouns when they are needed or helpful and to be certain that every pronoun has a clear antecedent (i.e. word or statement it points back to) and agrees with its antecedent in person, number and, if necessary, gender. Secondly, the use of pronouns helps maintain focus on the controlling idea throughout a paragraph.

It refers to nouns; this/that refers to statements

Consider the following text sample: Theme words are crucial for readers because readers depend on theme words to help them focus their attention on particular ideas in the beginning of sentences. Theme words make clear to readers what a whole passage is “about.” If readers feel that the sequence of theme words is coherent, then they will feel they are moving through a paragraph from a cumulatively coherent point of view. But if throughout the paragraph readers feel that its theme words shift in no clear order, then they have to begin each sentence without a clear context, from no coherent point of view. When that happens, readers feel that they lose focus and become disoriented.

In this text, pronouns are used to create cohesion; the antecedent of the personal pronoun they is the noun readers. The pronoun it usually has a noun as its antecedent. The antecedent of the pronoun that is the last if … then … construction (i.e. that refers to have to begin each sentence witout a clear focus). The pronouns this and that often have a statement (indeed, often a rheme) as their antecedent.

Make sure pronouns have clear anteced-ents

A pronoun must refer to one specific antecedent. Sometimes a vague pronoun antecedent occurs when a pronoun refers to one or several groups of words. If this happens, reference is not clear. An example to illustrate the point:

Patients with a latent disease may have to be monitored for several years because they are at risk of developing the active form of the disease. This diminishes over time.

The pronoun this has no clear antecedent. Indeed, it could point back to any of the nouns (latent disease, the need to monitor the disease, the risk of developing active disease). It is therefore necessary to clarify the antecedent in a revision (e.g. This risk diminishes over time or The need to monitor these patients diminishes over time).

Many non-native English speakers, e.g. Danish writers, would probably be inclined to use a relative sentence (which diminishes over time) instead of the second main sentence (This diminishes over time) in the sample text above. However, this would not solve the problem because the pronoun which has no clear antecedent in this text.

Turn vague pronouns into nouns

Ambiguous pronoun reference often appears in the form of two-sentence clusters in which the first sentence has two possible antecedents for the pronoun in the second sentence. Consider the ambiguous sentence: Inadequate training in PCR techniques resulted in poor data. This has been our most pervasive problem. Now consider the sentence without this ambiguity: Inadequate training in PCR technique resulted in poor data. Training inadequacies have been our most pervasive problem.

Be especially careful with the pronouns this, that, it and which, and make sure that the reader will be able to identify the antecedent. If there is any doubt, you should change vague pronoun antecedents by turning the pronoun into an adjective, replacing the pronoun with a noun or noun phrase, or revising the sentence more extensively.

Repeat key words to focus on the theme

Repetition of key words

Repetition of key words and phrases adds coherence to a paragraph by drawing the reader’s attention to the controlling idea of the paragraph. Let us again consider the same text sample, now from the perspective of cohesion through repetition of words (theme words and readers):

Theme words are crucial for readers because readers depend on theme words to help them focus their attention on particular ideas in the beginning of sentences. Theme words make clear to readers what a whole passage is “about.” If readers feel that the sequence of theme words is coherent, then they will feel they are moving through a paragraph from a cumulatively coherent point of view. But if throughout the paragraph readers feel that its theme words shift in no clear order, then they have to begin each sentence without a clear context, from no coherent point of view. When that happens, readers feel that they lose focus and become disoriented.

In this text, we see how the repetition of particular words (readers, theme words, passage/paragraph) draws our attention to the controlling idea of the paragraph. What the text also shows is that rather than using brief, simple sentences, the text is combined into longer, more developed sentences that are connected by connecting words.

Repetition helps the reader connect ideas

In scientific writing, repetition sharpens the focus. Repetition especially helps the reader to connect ideas that are physically separated in the text. For example: Other investigators have shown that microbial activity can cause immobilisation of labile soil phosphorus. Our results suggest that, indeed, microbial activity immobilizes the labile soil phosphorus. It is important to repeat key specialised terminology and to use synonyms only for variation of the non-specialised vocabulary.

English loves transition words

Conjunctions or transition words

English loves transition words because they tell readers how to receive new information and how new information relates to previous information, showing for instance sequence in time or space, logical order, amplification, accumulation, etc. They are essential not only because they connect ideas, but also because they introduce any changes or shifts in the text’s line of argument. We may say that the connecting words combine the text with our understanding of the world, i.e. cohesion and coherence combine.

Conjunctions have meaning and grammar

Transition words are mainly conjunctions (conjunctive adverbs or adverbial conjunctions) which have a particular meaning. They also have grammar in the sense that some are phrase connectors (e.g. in addition to expressing addition; despite, in spite of expressing contrast, etc.) that can be used only with phrases; others are subordinators linking clauses or dependent sentences to full sentences (e.g. although, even though, despite the fact that expressing contrast); and yet others are sentence connectors (e.g. moreover, furthermore expressing addition; however, nevertheless expressing contrast).

In the following text, the conjunctions (underlined) show how the sentences are connected (because expressing cause/effect; if/then expressing conditionality; but expressing contrast); when expressing time): Theme words are crucial for readers because readers depend on theme words to help them focus their attention on particular ideas in the beginning of sentences. Theme words make clear to readers what a whole passage is “about.” If readers feel that the sequence of theme words is coherent, then they will feel they are moving through a paragraph from a cumulatively coherent point of view. But if throughout the paragraph readers feel that its theme words shift in no clear order, then they have to begin each sentence without a clear context, from no coherent point of view. When that happens, readers feel that they lose focus and become disoriented.

Use “because”, not “since”, to express causality

Most conjunctions have a basic meaning, but some may mean different things. The word since, when used as a conjunction, has two meanings, one related to time and the other to cause. Since can be correctly used in either sense—the choice is a matter of style. For example, in this sentence since is used to indicate time: He had wanted to become a doctor since he graduated. In the next sentence since is used in to indicate cause: Since the data were incomplete, the paper was rejected. Sometimes, therefore, because is the better word to use to express cause, and if there is any chance that the reader could think that the word since refers to time when it in fact refers to cause, then use the word because.